Learn More About Antibiotic Options for Sinus Infections

Why Antibiotics Matter—And When They Don’t: Overview and Outline

Few ailments derail a week like a throbbing, pressure-filled sinus infection. Yet it’s easy to oversimplify the cure: many cases don’t need antibiotics at all. Most acute sinus infections follow a viral cold and improve on their own within 7–10 days. A smaller portion is truly bacterial—often estimated at a minority of cases—where antibiotics can help. Clues that point toward bacteria rather than a lingering virus include symptoms lasting more than 10 days without improvement, a severe start with high fever and notable facial pain or purulent discharge for several days, or the “double-worsening” pattern where things improve and then sharply deteriorate. Matching treatment to cause is the heart of good care and smart antibiotic use.

Before diving into specific medications, here’s the roadmap you’ll follow in this article:

– What sinus infections are and when antibiotics help

– First-line antibiotic choices and why they’re used

– Alternatives for allergies, pregnancy, or complications

– Benefits versus risks and how resistance shapes decisions

– Practical guidance and a concise conclusion you can act on

Why is this careful approach so important? Overuse of antibiotics can fuel resistance, making future infections harder to treat. It also exposes people to side effects without meaningful gain when the illness would have resolved independently. Evidence reviews suggest antibiotics produce modest improvements for uncomplicated cases, while supportive care alone often leads to recovery. That means timing, symptom pattern, and risk factors matter. For example, adults with persistent symptoms beyond 10 days or who experience double-worsening may be more likely to benefit from targeted antibiotics than someone with a milder viral course on day four.

As you read, keep two principles in mind:

– Personalized care matters: factors like age, other illnesses, medication allergies, and local resistance patterns shape choices.

– Safety first: seek urgent evaluation for warning signs such as vision changes, severe swelling around the eye, confusion, very high fever, or a stiff neck, which can signal complications.

This guide is educational and not a substitute for care from a licensed professional. Still, by understanding how clinicians think through sinus infections, you’ll be better prepared to discuss options, recognize when antibiotics are appropriate, and use them responsibly when they are truly indicated.

First‑Line Antibiotic Options and Why They’re Chosen

When a bacterial sinus infection is likely, many clinicians reach first for an aminopenicillin combined with a beta‑lactamase inhibitor. The reasoning is straightforward: common bacterial culprits include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Beta‑lactamase production is frequent in H. influenzae (often reported around one‑third of isolates) and very common in M. catarrhalis (typically the majority), which can neutralize plain penicillins. Adding a beta‑lactamase inhibitor broadens coverage to address these enzymes while maintaining activity against key respiratory pathogens.

Another widely used option in adults with certain penicillin allergies is doxycycline. It offers activity against many respiratory organisms and is taken orally, which is convenient for outpatient care. Doxycycline is not ideal for everyone, and its use depends on individual factors, but it provides a practical alternative in scenarios where penicillin-based therapy is unsuitable. In regions where resistance patterns are shifting, clinicians may adjust selections based on local antibiograms, weighing community data alongside patient history and severity.

Duration also matters. Many adults do well with a shorter course, frequently 5–7 days when symptoms are improving, while children often receive a longer course tailored to age and severity. Shorter effective durations reduce exposure to side effects and may help curb resistance. If symptoms aren’t improving after several days on therapy, clinicians may reassess the diagnosis, confirm adherence, consider resistant organisms, or look for noninfectious contributors such as severe allergies or dental sources.

Who might need broader coverage or higher dosing strategies?

– People with more severe illness at presentation

– Those with recent antibiotic use or recent hospitalization

– Individuals with certain chronic conditions that raise risk

– Residents in areas with documented higher resistance rates

In side‑by‑side comparisons, the aminopenicillin/beta‑lactamase‑inhibitor combination is favored for reliable activity against the organisms most often implicated in acute bacterial sinusitis, while doxycycline is valued for flexibility when allergies limit choices. Both approaches aim to treat likely pathogens without using unnecessarily broad agents. This balance—adequate coverage without overshooting—sits at the core of responsible prescribing and helps safeguard effectiveness for the future.

When First‑Line Isn’t a Fit: Alternatives and Special Cases

Real‑world care rarely follows a single script, and sinus infections are no exception. Some people can’t take standard first‑line therapy because of allergies, medication interactions, pregnancy, or prior side effects. In such cases, clinicians consider alternatives. In adults with true immediate‑type penicillin allergies, doxycycline is a common option. For those who cannot use that route, other classes may be considered based on severity and risk profile, but the decision requires careful judgment given potential adverse effects.

In children with non–type I penicillin allergy, a cephalosporin chosen for respiratory coverage—and sometimes combined with clindamycin for more reliable activity against certain streptococci—may be used under pediatric guidance. Macrolides and trimethoprim‑sulfamethoxazole are generally discouraged for empiric therapy in many regions because resistance among respiratory pathogens has been substantial, reducing the likelihood of benefit. These trends can shift over time and by location, which is why local resistance data and clinical guidelines are so influential in decision‑making.

Special populations add further nuance:

– Pregnancy: Many beta‑lactams are typically considered when antibiotics are indicated. Doxycycline and fluoroquinolones are usually avoided. Always coordinate with a prenatal clinician.

– Breastfeeding: Several agents have low breast milk concentrations and are often compatible; individualized advice is essential.

– Immunocompromised patients: Broader evaluation, possible imaging, and tailored regimens are common; complications can evolve more quickly.

– Chronic or recurrent symptoms: If symptoms persist beyond 12 weeks or repeatedly relapse, the condition may be chronic rhinosinusitis, which follows a different management path emphasizing inflammation control and sometimes specialist referral.

Know the red flags that warrant urgent reassessment:

– Eye symptoms such as swelling, impaired movement, or vision changes

– High fever with severe frontal headache or neck stiffness

– Facial swelling that’s spreading or very tender

– Neurologic changes like confusion or severe lethargy

– Worsening despite appropriate therapy

These signals point to potential complications such as orbital cellulitis or, rarely, intracranial extension—situations where imaging and specialist input may be critical. In short, alternatives exist for those who need them, but they are not interchangeable with first‑line therapy; each comes with trade‑offs in coverage, tolerability, and safety. Thoughtful selection—grounded in allergy history, risk factors, local resistance, and clinical severity—helps ensure that patients receive treatment that is both effective and appropriately cautious.

Benefits, Side Effects, and the Stewardship Balance

Patients understandably ask, “Will antibiotics actually help me feel better faster?” The answer is often “somewhat,” and context matters. Evidence syntheses of uncomplicated acute bacterial rhinosinusitis suggest antibiotics can improve cure or improvement rates compared with placebo, but the absolute gains are modest. Roughly, several additional people out of every hundred recover sooner with antibiotics, while a similar number experience side effects such as gastrointestinal upset, rash, or yeast overgrowth. That trade‑off is acceptable when bacterial infection is likely, less so when symptoms are early or mild and the chance of viral illness remains high.

Potential adverse effects vary by medication:

– Beta‑lactams: diarrhea, nausea, rash; rare allergic reactions

– Doxycycline: photosensitivity, stomach irritation; interactions with certain supplements that contain calcium, magnesium, or iron

– Broader‑spectrum agents: higher risk of collateral damage to the microbiome and, in some cases, serious but uncommon effects

Another concern is Clostridioides difficile infection, which can follow antibiotic exposure and cause significant diarrhea. While the risk is generally low in healthy outpatients, it rises with older age, prior antibiotic courses, and hospitalization. Antimicrobial stewardship—the practice of using the right drug, at the right dose, for the right duration—aims to capture the benefits while minimizing harms and preserving antibiotic effectiveness against resistant organisms.

Practical stewardship in sinusitis includes:

– Watchful waiting for select mild cases with reliable follow‑up

– Delayed prescriptions that are filled only if symptoms persist or worsen after a set period

– Shorter effective durations when patients are improving

– Reassessment if there’s no response after several days on therapy

Equally important is avoiding antibiotics for clear viral illness, not sharing leftover pills, and never pressuring a clinician to prescribe “just in case.” If started, complete the prescribed course unless your clinician advises otherwise. And if symptoms escalate—severe facial pain, high fever, or new eye/neurologic changes—seek care promptly. Used wisely, antibiotics can meaningfully help those who need them; used indiscriminately, they can cause avoidable side effects today and resistance problems tomorrow.

Practical Guidance and Conclusion: What This Means for You

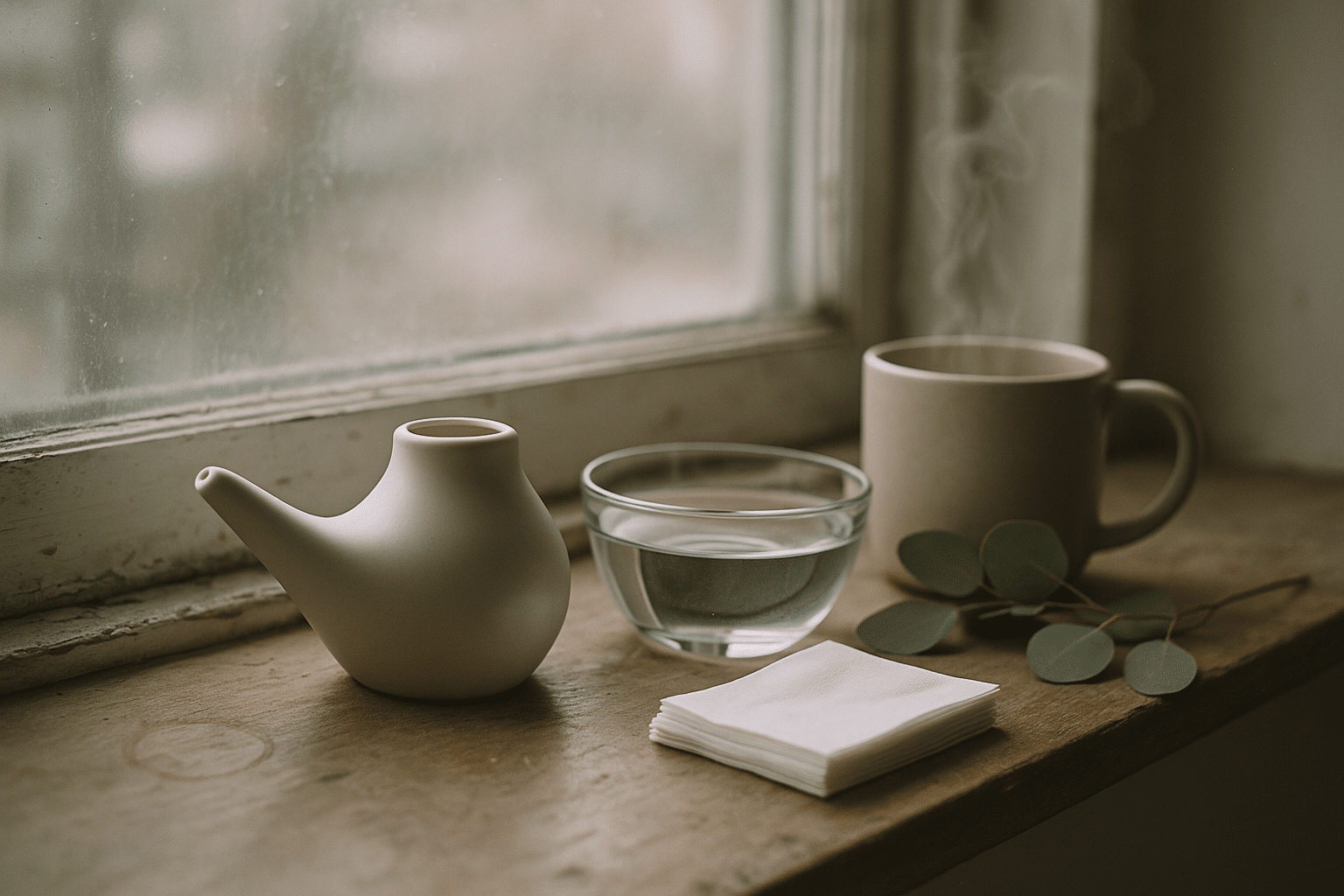

While antibiotics can be crucial for true bacterial sinus infections, symptom relief and prevention don’t begin or end with a prescription. Supportive care can ease the worst days and may reduce the need for antibiotics in milder cases. Consider these measures:

– Saline irrigation: Rinsing with sterile or previously boiled and cooled water can reduce mucus thickness and improve drainage.

– Intranasal corticosteroid sprays: Helpful when inflammation and allergies are part of the picture.

– Pain and fever control: Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti‑inflammatories as advised by your clinician.

– Short‑term decongestants: Topical agents can help for a couple of days, but extended use risks rebound congestion.

– Rest, hydration, and humidified air: Small comforts that add up.

Prevention deserves equal attention. Good hand hygiene, managing allergies, avoiding tobacco smoke, and keeping up‑to‑date with recommended vaccines may reduce the frequency and severity of upper respiratory infections that can evolve into sinusitis. Dental care can also matter because dental infections sometimes mimic or contribute to sinus symptoms. If you endure frequent episodes, tracking triggers—seasonal allergens, air travel, or workplace exposures—can help tailor strategies that cut recurrences.

Head into your next visit prepared with focused questions:

– Could watchful waiting work for my situation, and what symptom changes should trigger treatment?

– If antibiotics are appropriate, which option fits my history and local resistance patterns?

– What duration is planned, and when should I expect to feel noticeably better?

– How will we follow up if there’s no improvement by a certain day?

– Are there interactions or side effects I should watch for given my other medications?

Conclusion: If your symptoms are persistent, severe, or follow a classic double‑worsening pattern, antibiotics may offer a meaningful nudge toward recovery. If your illness is early, mild, or clearly viral, supportive care and time are often enough. The most effective path is a shared one: you describe your symptoms and goals; your clinician weighs risks, benefits, and local data; together you choose a plan. That partnership keeps you safer today and helps ensure antibiotics remain powerful allies when they are truly needed.