Has Anyone Recovered From Cirrhosis? Understanding Improvement, Management, and Outcomes

Introduction

Cirrhosis is one of those diagnoses that can feel like a slammed door—final, immovable, and heavy with implication. Yet, clinical experience and growing research tell a more layered story. While scar tissue in the liver tends to be permanent, the liver’s remarkable capacity to adapt means that function can improve, complications can recede, and in some cases the scarring itself can partially regress when the root cause is effectively treated. Understanding what “recovery” means—practically, medically, and emotionally—helps people set realistic goals and take steps that truly change outcomes.

Outline

– What “recovery” means in cirrhosis: definitions, stages, and the difference between symptom relief and tissue change

– Evidence that improvement happens: alcohol abstinence, antiviral therapy, autoimmune control, and metabolic care

– What tends to improve vs. what usually does not: symptoms, labs, imaging, and biopsy insights

– Evidence-based actions: treatments, lifestyle changes, and monitoring that support better outcomes

– When transplant enters the picture: timing, prognosis, and decision-making

What “Recovery” Means in Cirrhosis: Definitions, Stages, and What Can Improve

Cirrhosis describes advanced scarring of the liver, the endpoint of chronic injury from causes such as long-term alcohol use, viral hepatitis, autoimmune disease, or metabolic dysfunction. The word sounds absolute, but clinicians divide cirrhosis into compensated and decompensated stages. In compensated cirrhosis, the liver still performs essential tasks—processing nutrients, creating proteins like albumin, and detoxifying waste—without major complications. In decompensated cirrhosis, complications appear: fluid buildup (ascites), confusion from toxin buildup (hepatic encephalopathy), internal bleeding from enlarged veins (varices), jaundice, and kidney stress. Why this distinction matters: people with compensated cirrhosis often live many years, and with effective treatment of the cause, they may see meaningful improvement in quality of life and even partial regression of fibrosis in some cases.

Recovery, then, rarely means the liver returns to its untouched, pre-injury state. Rather, it often means stabilization or improvement across several dimensions:

– Symptoms: fatigue, concentration, abdominal discomfort, and exercise tolerance can improve with targeted care.

– Laboratory tests: albumin, bilirubin, INR, and platelet trends may move toward healthier ranges when the cause of injury is halted.

– Complications: portal pressure can decrease, reducing risks of ascites and bleeding; encephalopathy can be controlled and sometimes prevented.

– Structure: in a subset of patients, repeated injury calms enough for scar tissue to remodel, a process sometimes called regression of fibrosis.

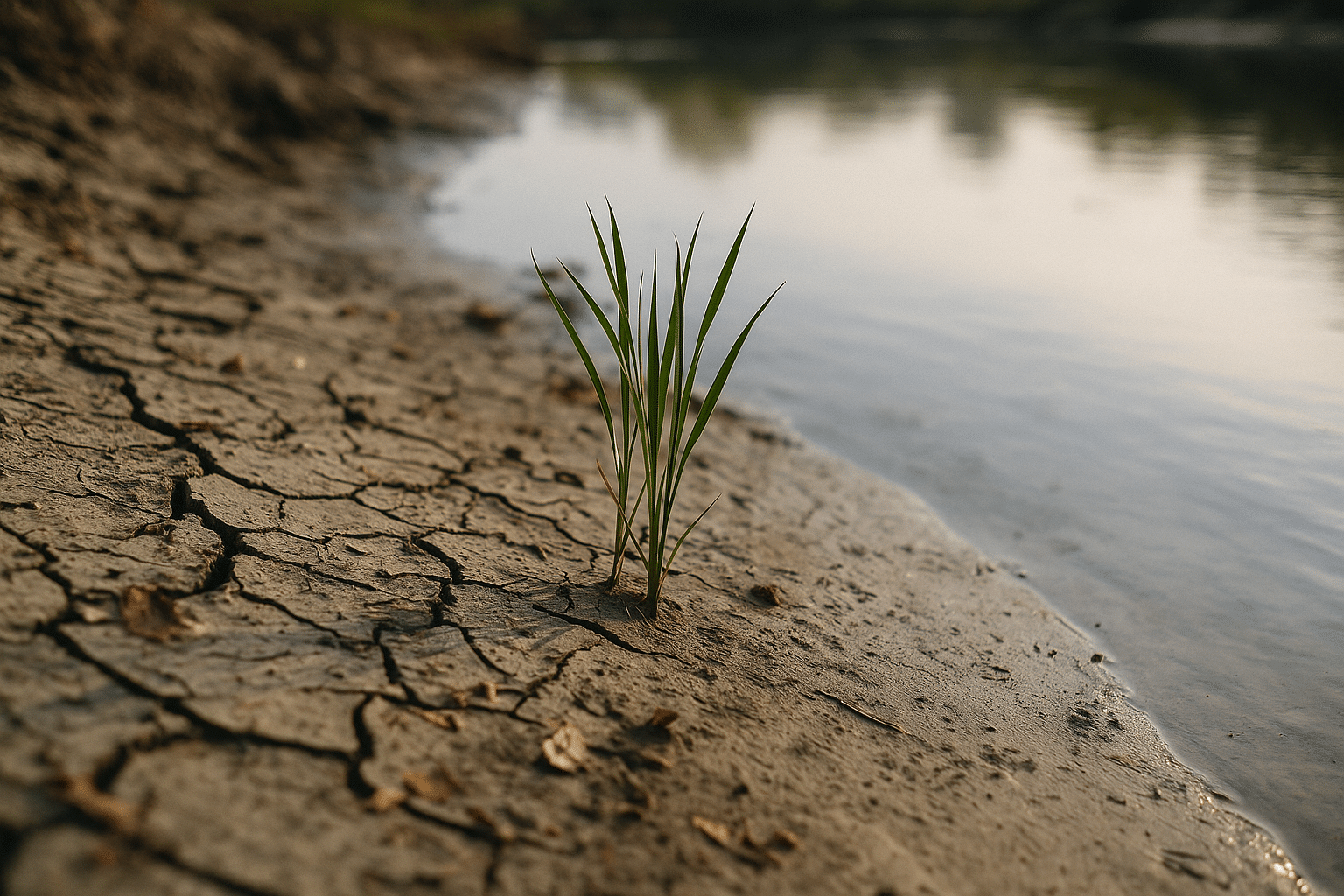

Two tools frame this journey: the Child-Pugh score (assessing severity via labs and complications) and the MELD score (a transplant-prioritization score reflecting short-term risk). Improving these scores is a practical marker of “recovery” in the real world. Think of the liver as a river delta; once channels silt up, they do not entirely revert, but if the storm stops and debris clears, new paths can form and flow steadies. That steadier flow—fewer complications, stronger lab numbers, and better day-to-day life—is what recovery usually looks like in cirrhosis.

Evidence and Real-World Stories: Who Has Shown Regression and How?

Evidence for improvement in cirrhosis has grown alongside therapies that remove or quiet the original insult. People with alcohol-associated cirrhosis who achieve sustained abstinence often experience striking gains: fluid retention eases, liver inflammation declines, and risks of bleeding and hospitalization drop. In large cohorts, abstinence is consistently linked to lower mortality and fewer decompensation events compared with continued drinking. While abstinence is not a guarantee of reversal, it is the single most powerful change for this group, and clinicians regularly witness patients move from unstable to steady when support, counseling, and time align.

Viral hepatitis offers another compelling proof point. For hepatitis C, modern direct-acting antivirals achieve cure rates above 90%. After cure, many patients with cirrhosis see improved lab profiles and reduced portal pressure; the likelihood of liver-related complications declines substantially, though not to zero. Studies report histologic fibrosis regression in a notable fraction of cured individuals, sometimes within a few years. For hepatitis B, long-term antiviral suppression lowers liver inflammation and can stabilize, and in some cases partially reverse, fibrotic change. The earlier the intervention relative to advanced decompensation, the more room there is for measurable recovery.

Autoimmune hepatitis responds in many patients to immunosuppressive therapy designed to calm immune-driven injury. When inflammation is controlled, liver tests often normalize and fibrosis can regress over time, especially in those treated before severe architectural distortion sets in. In metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (sometimes called NASH in prior terminology), weight loss of roughly 7–10% has been associated in clinical trials with resolution of active inflammation and measurable decreases in fibrosis stage for a meaningful proportion of participants. Bariatric procedures, where appropriate and safe, have also shown improvements in liver histology over the medium term. Across these scenarios, the arc is similar: remove the fuel feeding the fire, and the scarred “orchard” often starts bearing healthier fruit again.

What Improves and What Usually Does Not: Symptoms, Labs, Imaging, and Biopsy

Improvements in cirrhosis are detected through a blend of patient experience, laboratory results, imaging, and, when necessary, tissue evaluation. Symptoms can be a sensitive early barometer: less bloating, better sleep, steadier focus, and increased stamina often follow successful treatment of the cause. Encephalopathy episodes may become rarer and milder when triggers are controlled and gut-derived toxins are managed. Appetite can return with thoughtful nutrition, and muscle strength often rebounds when protein intake and exercise are optimized. Even small gains here matter because frailty independently predicts outcomes in cirrhosis.

Laboratory markers help track objective recovery:

– Rising albumin can indicate better synthetic function and nutrition.

– Falling bilirubin suggests improved bile handling and reduced liver stress.

– A steadier INR hints at stronger production of clotting factors.

– Platelet counts may increase if portal pressure falls and spleen sequestration eases.

Noninvasive imaging adds another layer. Ultrasound elastography (for example, vibration-controlled transient elastography) measures liver stiffness, which tends to drop when inflammation settles and, in some cases, when fibrosis remodels. Portal vein flow patterns and spleen size can also reflect shifting portal pressures. Endoscopy findings may evolve too; with lower portal pressure, varices can shrink or stabilize, reducing bleeding risk. Biopsy remains the definitive tool to stage fibrosis, though it is used selectively due to invasiveness and sampling variability. Notably, some elements tend to persist: once extensive architectural distortion has occurred, the liver may never look “normal” on imaging, and the lifetime risk of liver cancer remains elevated after viral cure or metabolic improvement, warranting ongoing surveillance. In short, improvement often appears as a mosaic—clearer labs, calmer scans, fewer complications—rather than a single dramatic transformation.

Evidence-Based Actions: Treatment, Lifestyle, and Monitoring That Support Better Outcomes

The path toward improvement in cirrhosis is built from many steady steps rather than a single leap. Treating the cause is foundational: complete alcohol abstinence when alcohol is the driver; antiviral therapy for hepatitis B or C as indicated; immunosuppression for autoimmune disease under specialist guidance; and weight-centered strategies for metabolic disease. Targeted therapies to manage complications—such as medications for encephalopathy or diuretics for ascites—can convert daily struggle into manageable routine, often revealing how much reserve the liver still possesses.

Lifestyle and preventive care are potent allies:

– Nutrition: aim for 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day of protein, with bedtime protein to limit overnight muscle loss; avoid prolonged fasting.

– Diet pattern: emphasize vegetables, legumes, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats; limit highly processed foods and added sugars.

– Sodium: if ascites is present or portal pressure is high, a modest sodium restriction is often recommended by clinicians.

– Physical activity: regular, moderate exercise supports muscle mass and insulin sensitivity; resistance work is especially helpful for sarcopenia.

– Vaccines: immunization against hepatitis A and B (if not immune) and routine vaccinations reduce preventable infections.

– Coffee: observational data link 2–3 cups daily with lower risk of progression and liver-related mortality; discuss individual tolerance.

– Safety: avoid raw shellfish due to infection risk; review all medications and supplements with a clinician to minimize liver stress.

Monitoring keeps progress on track. Periodic labs (including liver panel, INR, albumin), ultrasound elastography when useful, and endoscopic screening for varices in those at risk help catch changes early. For individuals with cirrhosis, regular surveillance imaging for liver cancer with ultrasound (with or without blood markers) is typically advised every six months, even after viral cure or weight loss success. Many people benefit from a structured care team—hepatology, nutrition, mental health, and primary care—because cirrhosis touches metabolism, immunity, and mood. The big picture: while there is no quick fix, consistent attention to cause, complications, and strength-building habits can translate into fewer hospital visits, steadier energy, and, for some, measurable regression of fibrosis over time.

When Transplant Enters the Picture: Prognosis, Timelines, and Making Decisions

Liver transplantation becomes relevant when decompensation persists despite optimal care, when quality of life suffers from recurrent complications, or when the MELD score signals high short-term risk. Early referral to a transplant center opens doors to evaluation, education, and strategies that may improve candidacy, such as optimizing nutrition and controlling infections or bleeding risks. Contrary to common fears, evaluation does not commit a person to surgery; instead, it clarifies options and timing. For some, stabilization during the workup delays or even negates the need for immediate listing.

Outcomes after transplant are generally strong. Across many regions, one-year survival commonly exceeds 85–90%, and five-year survival often reaches 70–75%, reflecting decades of advances in surgery, anesthesia, and post-transplant care. Beyond survival, improvements in daily function—walking, working, and eating without fear of sudden decompensation—are frequently reported. Living donor transplantation may be an option in select settings, potentially shortening wait times, while deceased donor allocation is typically guided by MELD score and urgency. Alongside transplant candidacy, palliative and supportive care can and should run in parallel, focusing on symptoms, goals, and dignity regardless of surgical plans.

Decision-making is rarely linear. Some individuals with compensated cirrhosis choose close monitoring and cause-directed therapy for years, experiencing gradual improvement and stable lives. Others with aggressive disease or late presentation need swift steps toward transplant to avoid repeated hospitalizations and life-threatening complications. Practical signals that it is time to discuss transplant include refractory ascites, recurring encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, recurrent bleeding from varices, or a MELD score persistently in the mid-teens or higher. The guiding principle is simple: choose the path that maximizes both length and quality of life, informed by clear data and aligned with personal values. In that framework, “recovery” can reasonably mean renewed stability with one’s native liver—or a decisive reset through transplantation.

Conclusion: A Realistic Map to Hope

Has anyone recovered from cirrhosis? Yes—if we define recovery as stabilization, fewer complications, stronger lab trends, and, in a subset, partial regression of fibrosis after the cause is treated. Scar tissue seldom disappears entirely, but the liver’s resilience, paired with modern therapies and steady habits, can change trajectories in powerful ways. For individuals facing cirrhosis today, the most reliable path forward blends cause-directed treatment, practical lifestyle shifts, vigilant monitoring, and timely consideration of transplant when needed. It is not a sprint or a miracle cure; it is a disciplined, hopeful journey in which many see life open back up—one measurable gain at a time.